This policy brief was originally written as a project for an internship at the New York City Office of the Public Advocate

The purpose of this policy brief is to outline various issues that are facing the CUNY system today, with a brief list of recommendations towards solving these problems. My brief conclusion contains a call to action, namely that in order for any positive change to take place, the CUNY community must prioritize self-organization and cohesion, as a community. The status of CUNY’s funding, being shared by the city and the state, complicates any discussion towards implementation of reforms. However, I hope this brief serves as a guide to the different challenges facing CUNY, and where some jumping off points for solutions may lie.

Background

The City University of New York’s legacy is in danger. Despite a slight uptick in the fall of 2023, CUNY enrollment numbers are still far below their pre-pandemic peak.1 Facilities are falling apart, with students and staff complaining of rodents, mold, and leaks; CUNY admits that only 24 out of its 300 buildings are “in a state of good repair.”2 Faculty, who have gone over a year and a half without a contract, decry the austerity regime that the university system has been forced to swallow.3 Clearly, something must be done. This policy brief will outline four key areas in need of reform within the CUNY system to ensure that the “People’s University” maintains its accessibility, and improves the lives of the many millions of New Yorkers who are its students, staff, faculty, and alumni.

Admissions and Stratification

CUNY traces its earliest history to the Free Academy, founded in 1847, with the explicit aim of educating “the children of the whole people,” regardless of class (though not regardless of race). As such, the Free Academy required no tuition.4 Today, City College (the direct descendent of the Free Academy) still labels itself the “Harvard of the Proletariat.”5 However, in the last forty-five years, CUNY has become more and more exclusive. This is the case as a whole, in terms of total entrants to the system, and internally, where students are sorted into schools with varying levels of resources, based on race and class.

For the first one hundred and twenty-nine years of CUNY’s history (including its preexistence as independent public colleges), students paid little or no tuition. However, enrollment at CUNY was largely limited to white students. In 1969, inspired by the wider civil rights movements and empowered by limited victories such as the SEEK Program, Black and Puerto Rican students led a movement to make CUNY more representative of the city it claimed to serve. City College was padlocked and occupied, and students lambasted the administration over the fact that Harlem’s population was 98% Black and Puerto Rican, while CCNY’s day students were 91% white.6 These student-activists secured the establishment of ethnic studies departments at various campuses, and critically, an open admissions policy. This policy was called for explicitly as a redress to underserved communities of color in New York, and it worked. The proportion of non-white freshmen at CUNY grew from 22% in 1969 to 70% by 1975. However, this golden age of access and opportunity was not to last. City and State officials took advantage of New York City’s financial crisis and hit CUNY hard; Skyrocketing tuition-free enrollments were an easy target. By summer of 1976, tuition was imposed, and admissions standards were increased, especially for the senior colleges.7

These financial and admissions restrictions had an immediate effect, and set the tone for future cutbacks and austerity measures. By the end of the 1970s, CUNY’s enrollment numbers declined by 62,000 and the 1980 entering class saw a 50% reduction in Latino and Black students.8 Less than twenty years later, CUNY was in Mayor Giuliani’s sights for another crackdown. Anne Paolucci, the Chair of the CUNY Board stated at a meeting that they were “cleaning out the four-year colleges and putting remediation where it belongs.” Twenty-four student and faculty protesters were arrested at the meeting. An unnamed CUNY official reportedly told journalist Bob Herbert that the board and the city may have been able to find middle ground, except that no one wanted to confront Mayor Giuliani’s ire.9 Remediation is an important aspect of many college students’ curricula, especially those that have come from NYC’s own underfunded public schools. To limit remediation to community colleges is to, in effect, restrict senior colleges to a select few.

After the Global Financial Crisis, this trend intensified. As affordability became increasingly important in the college search, CUNY found its classroom spots in high demand. As such, admissions standards were raised for senior colleges, based on standardized tests that serve as a filter for “accumulated opportunity” as much as they do for intellect. Between 2000 and 2012, CUNY created a system where White and Asian students ended up at the more prestigious senior colleges, while Black and Latino students were shunted to under-resourced community colleges.10 Furthermore, the population of the CUNY freshman class who are Black fell by proportion between 2001 and 2008, and even fell by absolute numbers between 2008 and 2010. The trend is even worse for top-tier CUNYs; the freshman class at Baruch fell from 12% Black in 2001 to 6% in 2012. Meanwhile, from 2002 to 2010, the number of Black high school graduates who took the SAT had only increased.11 All the while, community college populations in CUNY have surged, mostly driven by increases in Black and Latino students. CUNY community colleges, which are required to accept all NYC high school graduates, are not a bad option per se. However, they currently do not represent a promising route for students. CUNY community college freshmen have only an 8% chance of earning a bachelor’s degree after six years.12

Another equity issue can result from chronic understaffing. A report by the University Faculty Senate Budget Committee shows that not only have faculty per 1,000 full-time equivalent students fallen from 43 to 34 between 2003 and 2019, but the campuses that have higher proportions of Black and Hispanic students are more likely to have fewer faculty members per 1,000 full-time equivalent students. (Their analysis also includes SUNY schools.) The authors point out that this is not just an issue of quality of education, but could be a violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.13

Barriers Beyond Admissions

Once students do begin attending college, further barriers between them and success can quickly present themselves. CUNY schools pride themselves on their working-class character and student body from all backgrounds and life situations. However, work responsibilities represent a significant burden on many students. Per a 2016 survey, 50% of CUNY students work a job. Of those students, 53% of them work more than twenty hours per week. 37% of working students also report that working has a negative impact on their academics.14 Students are often told that earning their education is a full-time job. However, when over 25% of CUNY students work twenty or more hours a week, academics can easily fall by the wayside.

There have been attempts to mitigate the outside factors that limit student success. Accelerated Study in Associated Programs (ASAP) is an initiative at CUNY community colleges, designed to increase graduation rates and accelerate completion times. The program’s features include free tuition, financial assistance for textbooks, free metrocards, intensive advisement, and strong encouragement to complete an associate’s degree in three years.15 According to a 2013 study, the three-year graduation rate for ASAP students is 55%, double that of the student population at large (27%).16 Further study has concluded that not only is ASAP more beneficial towards student success, but it is also cost effective. Despite the high upfront costs, the improved success rate and time-to-completion lowers the cost-per-degree as compared to usual college services.17 That students with wraparound services have such higher rates of success illustrates the barriers that the student population at large faces.

State of Labor at CUNY

CUNY faculty have gone a year and a half without a contract. The Professional Staff Congress (PSC-CUNY) has been negotiating with CUNY management to try and secure a five-year contract, retroactive pay raises, and better treatment of adjuncts, among other issues.18 Professors are frustrated, and believe that the negotiations show management doesn’t have CUNY’s mission to the public in mind.19 This is a microcosm of a wider battle in higher education. Where colleges and universities were once places for ideas to be born and student minds to grow, now they have been recuperated into the profit-generating machine. To be clear, universities have always generated money for a select few, but the role of faculty as enablers of a production line-style curriculum is only becoming more common.20 One facet of this reorientation towards the profit motive is the growing plight of adjunct professors.

The adjunctification of the university is only the next step in the total commodification of American higher education. Between 1990 and 2012, the increase in the number of part-time faculty jobs in the United States was three times the increase in full-time positions. Thus, by 2015, 50% of the faculty workforce were adjuncts, and not on a tenure track.21 However, until recently, the CUNY system actually represented a bright spot in the fight for adjunct job security. In the last PSC contract, there was included a pilot program to give adjuncts three-year appointments, instead of hiring them on a semester by semester basis. This program was not only a victory for CUNY adjuncts, but served as a model for other faculty unions to build upon. However, in the latest round of contract negotiations, CUNY management is proposing a tightening of the eligibility requirements for adjuncts to receive multi-year appointments.22 According to PSC President James C. Davis, there are currently 2,400 adjuncts who have multi-year appointments under the current contract. Under CUNY management’s new proposal, just 300 of those adjuncts would be eligible to renew their appointments.23 CUNY management is not just preventing faculty from improving their working conditions, it is taking a revanchist position against the PSC’s previous gains.

Forced job insecurity is not the only tool CUNY management uses to keep teaching costs low. Understaffing is a persistent issue on campuses. York and Queens Colleges were faced with surprise layoffs in January, weeks before the start of the spring semester. These layoffs caused 18% of scheduled classes at York to be canceled at the last minute, throwing student schedules into disarray. CUNY Chancellor Felix Matos Rodriguez promptly told lawmakers “…we have made great strides, [but] there’s still more work to be done” to cut costs.24 The Chancellor told the Queens College PSC that the cuts were part of a deficit reduction plan designed to reduce costs on nine different campuses to address a decline in tuition income. However, as Queens College professor Kevin Birth points out, staffing reductions and last minute cuts in classes only further frustrate and demoralize students, which encourages students to abandon their studies and thus creates a greater reduction in tuition income.25

These cuts reduce the amount of time that professors have to interact with each student, and force faculty to work overtime to pick up the slack from vacant positions. A survey of non-instructional titles represented by the PSC showed that over the last four years, workloads have increased for 85% of library faculty, laboratory technicians, and Higher Education Officers. The top two reasons for the increased workloads are understaffing and changes in the nature of the job, with 71% and 51% of staff reporting those as factors.26 A transition towards an increased reliance on technology and the internet in academia was only hastened by the pandemic. When faculty are already complaining about drowning in new job responsibilities, that is not the time to further cut staff. As mentioned above, understaffing can also present itself as an equity issue. CUNY campuses that have more Black and Hispanic students, tend to have fewer faculty members per 1,000 full-time-equivalent students.27 If the main concern for CUNY management is long-term financial stability, cutting classes and spreading faculty thin will only decrease student satisfaction and make CUNY a less attractive destination for students and reduce the pot of tuition income.

CUNY’s Administration and Leadership

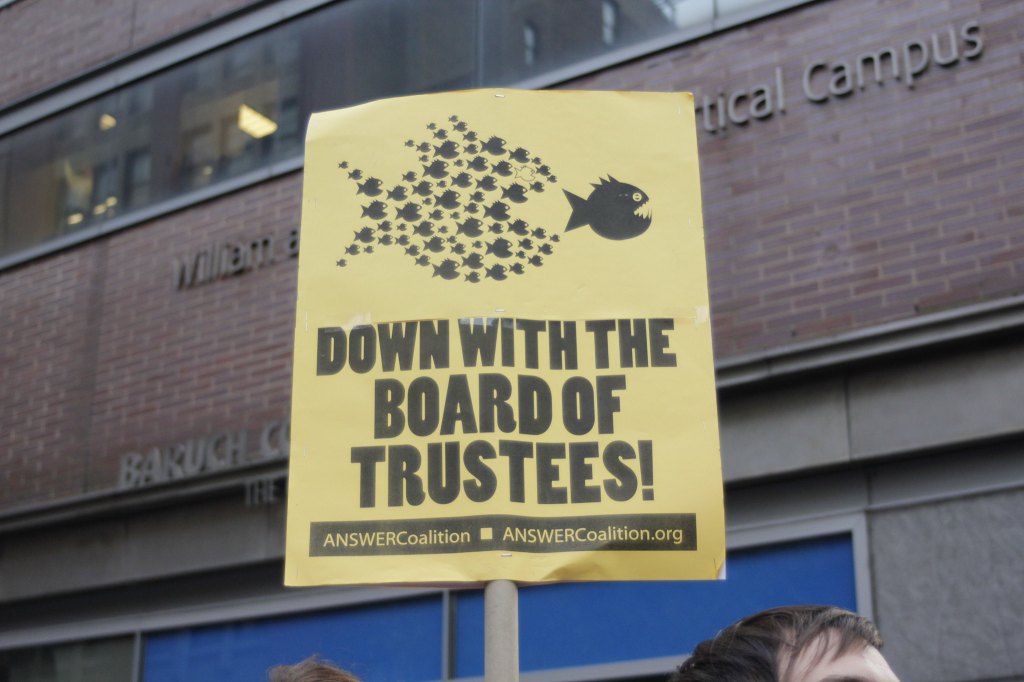

As discussed in the previous section, CUNY management has wildly different priorities than students and faculty. The CUNY Board of Trustees is an unaccountable group largely appointed by the governor and the mayor. Only two of seventeen trustees are in some way elected: the chairs of the University Faculty Senate and the University Student Senate.28 The responsibilities of the Board include the appointment of the CUNY Chancellor, currently Felix Matos Rodriguez. The Board also has final approval power over such decisions as promotions, reappointments, and hiring of senior staff (including university presidents), infrastructure projects, and changes to degree programs.29

The Chair of the Board of Trustees is William C. Thompson, a former NYC Comptroller who came under fire for soliciting campaign donations from financiers who sought business with the city’s various pension funds which he controlled.30 Thompson is now a Partner and an executive at Siebert Cisneros Shank & Co., an investment firm whose services include managing stock buybacks and SPACs.31 Other Trustees include executives who work for health insurance companies, developers, and Coca-Cola.32 Another Trustee, Robert Mujica, serves as Executive Director of the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, an unelected fiscal board charged with managing Puerto Rico’s debt crisis by way of an austerity regime including privatization, union busting, and cutting pensions and university budgets, with no popular oversight. (The $625,000 salary Mujica draws as Executive Director seems to be safe from cuts.)33 Just because many Trustees are CUNY grads, or their backgrounds are in philanthropy or public administration, does not mean their interests align with CUNY students and faculty. Indeed, it seems as if to be a CUNY Trustee one must first achieve a class position that is necessarily removed from the majority of the CUNY community.

Instead of seeing students as people who come to school free to explore different academic pursuits, they are commodities who need to be put through production as quickly, cheaply, and efficiently as possible.34 Despite faculty’s complaints about class sizes and increased workload, CUNY leadership’s financial plans include “efficient” scheduling to increase the number of students per class, even suggesting that classroom expansions should be prioritized for capital investment. Other strategies include increasing collections enforcement on unpaid tuition and potentially opening up CUNY property to development in partnership with private interests. Current proposals by administration include changing University Presidents’ job descriptions from “Principal Academic Officer” to “Chief Executive Officer,” and shifting decision making power over the hiring, recruitment, promotion, and scheduling of faculty away from department heads.35 Increasing class sizes, cracking down on tuition collections, and centralizing or rationalizing department decision making are not examples of proposals that serve the CUNY community.

For a crystalline example of the divergence between CUNY leadership and the community, one need look no further than the CUNY Gaza Solidarity Encampment and the actions by CUNY administrators in response to it. Students, faculty, and allied community members set up camp on a courtyard within City College’s publicly accessible campus. Five days later, after sporadic sparring, the NYPD cracked down and arrested 173 people in and around the CCNY campus. The mass-arrest included batons and pepper spray, and resulted in injuries including a broken ankle and multiple broken teeth.36 Opinions on Israel’s war in Gaza may vary among CUNY community members, but it is safe to say that students and faculty who are peacefully occupying a publicly accessible lawn on a CUNY campus do not deserve to be terrorized by a militarized police force. One of the demands of the encampment was a demilitarization of campuses, a demand which was validated by the violent mass arrest. However, weeks later, the CUNY Board of Trustees decided to double down.

At a May 20 meeting of the CUNY Board of Trustees, the Trustees voted to authorize an extra $4 million towards security on campuses. The firm, which has ties to Israel, also claimed students were using “Guerilla Warfare tactics.”37 The Board also approved an extra $2 million for security equipment and fences. This meeting came a week after the Board’s so-called “public” hearing, which they moved online at the last minute, and restricted testimony to only those who had previously registered.38 Regardless of one’s opinion on encampments and student activism, it is clearly not in the interest of the CUNY community to spend multiple more millions of dollars on policing, all the while stonewalling faculty seeking a contract, and refusing to fix crumbling school buildings.

This incident is not distinct from things like labor issues and a student retention crisis. Indeed, it is part of a continuous pattern of the board acting in its own interests, with the only recourse for the community being public protest, which may or may not end in violence towards students and faculty. PSC has been demonstrating in vain since the end of their last contract. When the board meets on pre-registered zoom, or behind closed doors, the community is robbed of what little input they may have.

Recommendations:

1. Return CUNY to Open Admissions and Tuition Free status

There are multiple groups working towards free tuition, most notably the CUNY Rising Alliance.39 This group, a coalition of student, labor, and community organizations, is working with State Senator Andrew Gounardes and Assemblymember Karina Reyes to advance a bill at the state level.40

Open admissions must be reinstated for the same reasons it was originally proposed: to help close the race and class gaps between the “premier” CUNY’s and the community colleges.41 Open admissions allowed thousands of New Yorkers to go to college who otherwise wouldn’t have. Graduates who were admitted under open admissions generated a lifetime economic activity of $2 billion more (in 1996 dollars, $4 billion in 2024) than if open admissions were not instituted.42

These policies represent an investment in NYC. Per a City Comptroller study from April 2024, after 5 years, 85% of CUNY grads remain in state. After 10 years, it’s 80%. Additionally, half of all CUNY grads go on to work in health care, social assistance, education, and public administration.43

2. Increase Services for Students

The ratio of mental health counselors to students should be increased, in order to bring CUNY up to national standards.44 Beyond that, the efficacy of the ASAP Program demonstrates the immense benefit that wraparound services bring to CUNY students. All CUNY students should be able to take advantage of those services, which include free Metrocards, textbook assistance, increased availability of tutors, and more intensive advisement.45 Again, the current cost-per-degree for ASAP students in community colleges is lower than the student body at large; The program is clearly not just a money sink.46

3. Improve Working Conditions for Faculty

PSC-CUNY is in desperate need of a contract.47 A year-and-a-half is too long for any workforce, especially one whose bargaining rights are already severely constrained by the Taylor Law. Additionally, adjunct positions should maintain their protections, and more tenure lines for professors should be instituted.48

4. Institute Self-Government for CUNY Schools

CUNY leadership’s vision for the university’s short-term future must be prevented. Up coming changes proposed by CUNY administration include:49

- Changing the job description of university presidents from “principal academic officer” to “chief executive officer.”

- Increasing administrative control over recruitment, evaluation, and scheduling of faculty, taking power away from democratically elected department chairs.

- Further increasing class sizes

- Prioritizing collections enforcement on unpaid tuition

First of all, everyday decision-making power must be shared with faculty, who are in a better position to evaluate student needs.50 Another possibility is the elimination of standardized grading and faculty evaluations to limit administrative ability to judge “outcomes” from the top down. These measures would ensure that faculty are in direct control of how classes are operated.51

However, on a more fundamental level, CUNY’s governance structure must be transformed from so-called “shared” governance to democratic governance, as modeled by many universities in Europe and South America.52 Common features of a democratically governed university include democratic election of university leadership by faculty, students, and staff, and empowerment of faculty unions.

Conclusion

In my opinion, many of CUNY’s current problems are downstream of its governance structure. No matter the specific issues, the throughline of faculty complaints are the diverging interests of the Board of Trustees and the CUNY community. As such, I would argue that the most important of the above recommendations is 4: Institute Self-Government for CUNY Schools.

In any case, none of these changes will happen quickly, and none will happen without energy and organization by students, staff, and faculty. A preliminary call to action: talk to people you know on campus, in your classes, and in your life outside of class. Discuss the issues above, and any other issues that community members raise. The CUNY community must be galvanized as a social force. The more the CUNY community takes ownership of their school not just as a place where you go to sit in a classroom, but as a center of community, social organization, and knowledge production, the more motivated and better positioned the community will be to take action and enact change on their own campuses.

References

- Elsen-Rooney, Michael, and Alex Zimmerman. “CUNY sees slight enrollment uptick, but big challenges remain,” Chalkbeat (2023) ↩︎

- Paul, Ari. “PSC to council: Fix our buildings,” Clarion (2024) ↩︎

- Kang, Susan. “CUNY Is the People’s University. Austerity Is Killing It,” Jacobin (2023) ↩︎

- “Origins and Formative Years,” CUNY (n.d.) ↩︎

- “Our History,” CCNY (2023) ↩︎

- Steinberg, Stephen. “Revisiting open admissions at CUNY,” Clarion (2018) ↩︎

- “1970-1977 Open Admissions – Fiscal Crisis – State Takeover,” CUNY Digital History Archive, (n.d.) ↩︎

- Steinberg, (2018) ↩︎

- Herbert, Bob. “In America; Cleansing CUNY,” the New York Times (1998) ↩︎

- Hancock, Lynnell, and Marilyn Kolodner, “What it takes to get into New York City’s best public colleges.” Hechinger Report, (2015). ↩︎

- Treschan, Lazar, and Apurva Mehrota. “Unintended Impacts.” Community Service Society, (2012) ↩︎

- Hancock and Kolodner, (2015) ↩︎

- Benton, Ned, et al., “The Faculty Gap: Comparison of SUNY and CUNY Senior College Faculty/Student Ratios,” UFS Budget Committee, (2021) ↩︎

- “2016 Student Experience Survey.” Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, (2016). ↩︎

- Domanico, Ray, Joydeep Roy, and Yolanda Smith. “ANALYSIS OF THE POTENTIAL COST….” Independent Budget Office, (2015) ↩︎

- Linderman, Donna, and Zineta Kolenovic. “Moving the Completion Needle at Community Colleges,” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, (2013) ↩︎

- Scrivener, Susan et al. “Doubling Graduation Rates,” p. 90. MDRC, (2015) ↩︎

- “Contrasting Visions for CUNY Employees,” PSC-CUNY (n.d.) ↩︎

- Paul, Ari. “PSC: Contract Time is Now,” Clarion, (2024) ↩︎

- Misse, Blanca, and James Martel, “For Democratic Governance of Universities: The Case for Administrative Abolition,” Theory & Event, (2024) ↩︎

- Anthony, Wes, et al. “The Plight of Adjuncts in Higher Education,” Practitioner to Practitioner, (2020) ↩︎

- Paul, Ari, “Demanding job security for adjuncts,” Clarion, (2024) ↩︎

- Lewis, Crystal, “CUNY union pledges to fight proposed changes that threaten adjunct job security.” The Chief, (2024). ↩︎

- Editorial Board, “CUNY leaders must fight harder against budget cuts,” The Ticker, (2024) ↩︎

- Paul, Ari, “CUNY imposes citywide devastation,” Clarion, (2024) ↩︎

- Paul, Ari, “Staff say they’re overworked: survey,” Clarion, (2024) ↩︎

- Benton et al., (2021) ↩︎

- Hassan, Varisha. “The CUNY Board of Trustees: The Basics and Why They Matter,” The Knight News, (2024) ↩︎

- “Who Are the CUNY Board of Trustees?,” The Brooklyn Vanguard, (2021). ↩︎

- Halbfinger, David M., “As Pension Chief, Thompson Gave Work to Donors,” The New York Times, (2013) ↩︎

- “Corporate Experience,” Siebert Williams Shank (n.d.);

Lee, Peter, “Siebert Williams Shank grows far beyond municipal finance,” Euromoney, (2021). ↩︎ - “The Board of Trustees,” CUNY, (n.d.) ↩︎

- Vela-Cordova, Ramon, “The Unelected Board Governing Puerto Rico Will Continue to Operate in Secret,”

Jacobin, (2023). ↩︎ - Clarion Staff, “From the Streets to the Boardroom,” Clarion, (2024). ↩︎

- p. 37, “Stabilizing the University’s Finances,” City University of New York, (2024);

Paul, Ari. “PSC: Contract Time is Now,” Clarion, (2024) ↩︎ - Alfred, Tsehai, Surina Venkat and Chimene Keys. “NYPD arrests at least 173 protesters inside and outside City College, sweeps encampment,” Columbia Spectator, (2024);

Izar, Kimberley, “‘We will keep escalating’: The aftermath of CUNY’s pro-Palestine crackdown,” Prism, (2024) ↩︎ - Marich, Melanie, and Luca GoldMansour, “CUNY Gave $4 Million Contract to Security Firm That Claims Protesters Are Using ‘Guerrilla Warfare Tactics’,” Hell Gate, (2024) ↩︎

- Izar, (2024) ↩︎

- “Who We Are” CUNY Rising Alliance ↩︎

- Gounardes, Andrew, “Senate Bill S2146A”; Reyes, Karina, “Assembly Bill A4425A”. ↩︎

- Steinberg, (2018) ↩︎

- Arenson, Karen W., “Study Details CUNY Successes From Open-Admissions Policy,” New York Times, (1996). ↩︎

- “Spotlight: CUNY and the New York City Economy,” NYC Comptroller, (2024). ↩︎

- “New Deal 4 CUNY,” CUNY Rising Alliance. ↩︎

- Domanico, Ray, Joydeep Roy, and Yolanda Smith. “ANALYSIS OF THE POTENTIAL COST….” Independent Budget Office, (2015). ↩︎

- Scrivener, Susan et al. “Doubling Graduation Rates,” p. 90. MDRC, (2015). ↩︎

- “Summer Contract Campaign,” PSC-CUNY;

“New Deal 4 CUNY,” CUNY Rising Alliance. ↩︎ - Misse, Blanca, and James Martel, “For Democratic Governance of Universities: The Case for Administrative Abolition,” Theory & Event, (2024), p. 24;

“New Deal 4 CUNY,” CUNY Rising Alliance. ↩︎ - Paul, Ari. “PSC: Contract Time is Now,” Clarion, (2024);

“Stabilizing the University’s Finances,” p. 37, City University of New York, (2024). ↩︎ - Paul, Ari, “Is CUNY too centralized?,” Clarion, (2024). ↩︎

- Misse, Blanca, and James Martel, “For Democratic Governance of Universities: The Case for Administrative Abolition,” Theory & Event, (2024), p. 24. ↩︎

- Jean-Francois, Emmanuel, “From “Shared Governance” to Democratic Self-Rule in Public Higher Education,” Socialist Forum, (2021). ↩︎

Leave a comment