This piece was originally written as an essay for a course at John Jay College taught by Matt Rosales.

Introduction: Uber’s Grand Heist

Malang Gassama’s life was turned upside down after he learned that $25,000 had been stolen from him. He later learned that he was one of more than one hundred thousand New Yorkers who had been victimized in a multi-year crime spree, amounting to damages in the hundreds of millions of dollars (Office of the New York Attorney General, 2023). The perpetrator of this crime was Gassama’s employer, Silicon Valley darling Uber. In 2023, the popular ride-sharing company settled with New York State to pay $290 million in back pay to drivers that had been taken advantage of by Uber’s unfair, byzantine, and ultimately illegal payment system. Between 2014 and 2017 Uber was able to steal hundreds of millions of dollars, and while the company did have to pay back some drivers, they successfully avoided an admission of fault or punishment for the executives who make the decisions, let alone jail time (Browning & Ley, 2023).

Any outcome that transfers hundreds of millions of dollars from a corporation to the workers they exploit is no doubt a victory, but this settlement is just one battle between the rideshare app and local governments, with workers caught in the middle. Uber’s business model was and is still dependent on a precarious, low-paid workforce, most of whom will not enjoy the improved working conditions the New York Attorney General fought for. Furthermore, the headline $290 million payment is just that—a headline—as long as workers are obligated to opt into a complicated settlement scheme, which at best is too little, too late, and at worst represents an opportunity for Uber to once again take advantage of drivers with few financial or legal resources. The case of Uber’s wage theft represents a partial victory, and a prism through which the interconnected worlds of white-collar crime, labor relations, and workplace regulation all coalesce.

The Regulatory Environment for Rideshares in New York City

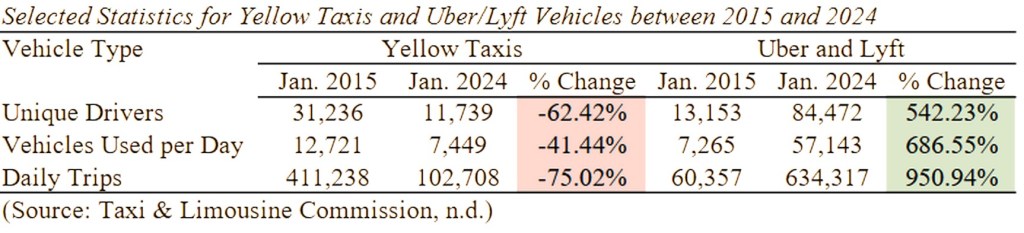

One of the most familiar and enduring symbols of New York City is the yellow taxi. For decades, it was the best and fastest way for carless locals and tourists alike to navigate New York. With one look at New York City’s streets today, however, it is clear that taxis have lost their luster. Now, the streets are a sea of generic black SUVs and gray sedans, all of which have license plates starting with “T” and ending with “C.” These are rideshares officially licensed as “For-Hire Vehicles” by the NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission, the regulating body of all cars that take paid passengers. On the average day in January of 2015, New York was served by 12,721 yellow taxis and 7,265 Uber or Lyft vehicles. By January of 2024, the number of yellow taxis used each day had decreased by over 40%, to 7,449. Meanwhile, the number of Uber and Lyft vehicles on the road each day increased by almost 700% to 57,143 (Table 1). This massive shift in NYC’s transportation economy must also be contextualized in the boom and bust of the taxi medallion market.

New York’s taxi industry has been regulated since 1937 by way of a limited number of taxi medallions, which are essentially licenses to operate a cab. The TLC decides how many medallions exist, and they can be freely bought or sold in an open market. Over the decades, a smaller number of taxi fleet operators bought up a larger share of the medallions, and the price went from a relatively stable $200,000 in the late ‘90s to over $1 million in 2014. Independent drivers, often immigrants and workers with few financial resources, took out predatory loans to cover the cost of a medallion, and once the bubble burst and the value of the medallions plunged, driver bankruptcies and suicides were epidemic (Rosenthal, 2019a). While many blamed the rise of Uber and other rideshares for the bust, the medallion market was artificially inflated by banks and lenders to the point that a crisis was inevitable (Paybarah, 2019). City and state officials chose not to intervene in the market, despite years of red flags. In 2010, a city analyst realized that a bubble was forming, and warned that if the city did not act, a burst was unavoidable. Inspectors at the state and federal level also reported to their respective agencies that these loans were predatory, and the medallion industry was clearly primed for collapse. However, these voices were ignored, and New York City sleepwalked into a crisis. Reporter Brian Rosenthal (2019b) positions this failure by the city and state in the long, sordid, and corrupt history of the TLC. No matter the cause, the taxi industry’s pain was Uber’s chance for plenty.

While the taxi industry was struggling with a financial crisis, and an ever-present hard cap on the physical number of cabs on the road, Uber consolidated its hold on the market. Mayor Bill DeBlasio tried and failed to institute a cap on rideshare vehicles in 2015. Instead, Uber was able to use its influence in the City Council to get DeBlasio to agree to a toothless compromise, allowing Uber to continue operating freely (Griswold, 2015). By August of 2018, when a cap was finally instituted by the New York City Council, Uber and Lyft were making 642,341 daily trips, well over double the 253,182 daily trips that New Yorkers took in yellow taxis (Taxi & Limousine Commission, n.d.). This cap was partially lifted in 2023, when the TLC announced that they would grant an unlimited number of rideshare licenses to electric vehicles, as a part of NYC’s broader push towards reducing its carbon emissions. The TLC had also been licensing wheelchair-accessible vehicles since 2018 (Lehrer, 2023). While the restriction of new licenses to electric or wheelchair-accessible vehicles tempers the ability of Uber drivers to flood the market as they did before there was any cap, any increase in rideshare vehicles lowers the earning potential of all drivers, whether they are driving a yellow taxi or an Uber.

For a wide swath of New Yorkers, the TLC’s decisions are not just another headline. They can be a deciding factor in shaping an Uber driver’s career, or they can send an immigrant taxi driver into hopeless debt. Uber engaged with the TLC in bad faith many times, as will be detailed in the next section. But one of the reasons that Uber was able to thrive in New York City is the TLC’s penchant for causing chaos in the transportation industry. Whether presiding over a lending market catastrophe, or caving to the pressures of private corporations, the TLC cannot seem to keep itself from causing trouble. As a VC-backed app seeking to disrupt a market, Uber could not have found a more disordered market to wreak havoc upon.

Uber in New York: Crash Landing, Growing Pains, and Wage Theft

Uber had its New York debut in May of 2011, and it didn’t take long for Travis Kalanick, founder and then-CEO, to attract headlines for his swashbuckling attitude towards local regulation. Already, the year before, Uber had run into trouble with the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which was resolved by the firm dropping “Cab” from its original name, “UberCab” (Wortham, 2011). Kalanick’s headaches continued in New York. After attempting to integrate the Uber app directly into medallion taxicabs, the TLC promptly prohibited the app’s use by yellow-taxi drivers and customers. Kalanick was not happy with this hiccup, claiming that NYC was not living up to its desire to be a technological hub (Flegenheimer, 2012a). Despite the TLC’s warning that use of the app was against the law, Uber continued to operate in New York’s yellow taxis for another six weeks, before Kalanick pulled the service. He also accused the TLC of privately acknowledging that Uber’s operations in the city were legal, which a TLC spokesman quickly denied (Flegenheimer, 2012b). Just a month later, the CEO defended Uber’s strategy of entering markets first and considering regulations later, going as far as to say that “if you put yourself in the position to ask for something … you’ll find you’ll never be able to roll out” (quoted in Chen, 2012). Clearly, Kalanick preferred not to ask for things, but to go ahead and take.

However, by 2015, Uber had cemented its place as the dominant rideshare service in New York City and beyond (Griswold, 2015). The company, after years of battle with the TLC, found itself in a detente with the city. From here on, the company’s main concern was its self-inflicted PR debacles, including a toxic workplace culture and a scandal over an executive digging up dirt on critical journalists (Isaac, 2017). Once Uber got what it wanted from local regulators, the firm sought a new source from which to extract surplus value: its own drivers.

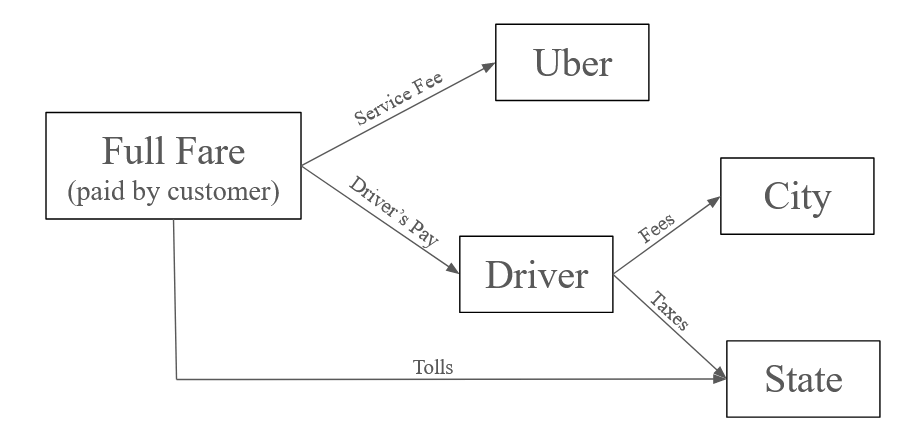

Uber’s business model is that of a market-maker. Uber connects drivers with passengers and sets fares using a dynamic scale based on supply and demand. Uber then takes a cut from the fare the customer pays the driver, which is how they make their money. Uber’s terms of service dictated that their cut would be calculated on the net fare, after required taxes and fees had been accounted for. However, in 2017, Uber admitted that it had been misapplying its commission system and had accidentally been taking more than their fair share of drivers’ pay since 2014 (Offenhartz, 2017). The mistake was tantamount to a few extra percentage points of the full fare being taken by Uber. However, it quickly became clear that this relatively small admission was nothing in comparison to the real scandal: Uber drivers like Inderjeet Parmar alleged that Uber wasn’t just taking their commission on the pre-tax fare, but also, they were paying fees and taxes solely out of the drivers’ share of the fare.

Parmar was reimbursed $4500 by Uber for the commission error, but Parmar was also owed another $14,500 for the state taxes and city fees he was wrongfully charged. Tim Cavaretta, another New York driver, alleged that Uber was remedying the smaller issue to appease drivers from pursuing the larger theft (Conger, 2017). A 2016 lawsuit by the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) raised the issue, and declared it wage theft. Documents and receipts analyzed by the New York Times supported NYTWA’s case. The Times also concluded that, contrary to the company’s public statements, Uber had known about the relatively minor commission issue for years, and yet failed to fix their mistake(Scheiber, 2017b). Further reporting by the Times revealed that an anonymous Uber whistleblower confirmed that the rideshare company had known about the commission issue since at least 2015. In the same story, it was reported that NYTWA had raised the sales tax issue to the Cuomo administration in October of 2015, and were met with little interest (Scheiber, 2017b). It was this egregious violation of their contract with drivers and their own terms of service that would end up costing Uber hundreds of millions of dollars in penalties, and countless millions more in future higher labor costs.

The Heavy Hand of the Law

In November of 2023, New York Attorney General Letitia James finished a multi-year investigation into Uber and Lyft’s business practices, stemming from NYTWA’s advocacy. James’ investigation concluded that Uber had indeed wrongfully charged drivers taxes and fees, which amounted to a theft of 11.4% of the driver’s rightful wage (Office of the New York Attorney General, 2023). Wage theft is a crime that is committed in a myriad of ways: underpaying workers, forcing employees to work off the clock, and misapplying overtime rules are just some forms it takes. However, according to Economic Policy Institute, it is a crime that robs American workers of as much as $50 billion every year, a number higher than all robberies, burglaries, and car thefts combined (Isser, 2023). Despite the fact that wage theft is a difficult crime to try, Letitia James made an example out of Uber.

The AG’s investigation ended in a massive settlement, and the headline figure was the $290 million that Uber had agreed to pay back to drivers. Additionally, Uber and other rideshare companies would be required to conform to a statewide minimum wage of $26 an hour, and allow drivers to accrue sick hours (Office of the New York Attorney General, 2023). These concessions are good news for drivers, and will hopefully prevent Uber from committing similar crimes in New York. However, this settlement is not a panacea. For one, drivers must opt in to the settlement fund to claim their reimbursement (Chen & Khafagy, 2023). This could prevent drivers who no longer live in New York, or are otherwise not aware of the news, from claiming their rightful pay. Given that this crime stretches back ten years, some drivers who are owed money may even be deceased, leaving their family to have to opt in on their behalf, another layer of difficulty. A second issue with the settlement has to do with timing. Certainly, restitution is better late than never, but drivers struggle to make ends meet, and many have had to put life plans on hold due to being underpaid. Malang Gassama, who drove for Uber and Lyft, said if he was paid what he was owed, he could have funded his wife’s business, sent money to family in Africa, and even kept his kids in their karate lessons (Office of the New York Attorney General, 2023). He may soon get the $25,000 he is owed, but he has already been denied the ability to use that money how he might have wanted to. This delay is exacerbated by the fact that the settlement fund will not begin paying out until 2025 (Chen & Khafagy, 2023).

Even in victory, the effects of Uber’s theft cannot be ignored. The economic effects of the crime are clearly the most direct. Drivers, even when they eventually are made whole, lose the opportunity to invest their money. Medical debts, family needs, school tuition, and many other expenses can be time-sensitive, and restitution ten years later could be far too late. The more deleterious effects of Uber’s crime are in the political sphere. NYTWA raised the issue of wage theft to New York State years before any action was taken to investigate Uber. Richard Emery, who had previously litigated a case with similar merits as Uber’s wage theft case, speculated that the state may have felt little incentive to try the case as long as they were getting their tax money (Scheiber, 2017a). While the Attorney General clearly came through for drivers in the end, that the state initially did nothing is severely damaging to the public trust. Finally, a social effect of Uber’s crime includes eroding the lives of drivers and their families. Wage theft means less income for already precarious New York families, which can have long term effects on how child development, and whether families can live comfortably or have food security. A city with more wage theft is a city with more crime, more suffering, and less community.

Uber took advantage of thousands of its workers in New York, and the financial impact that its wage theft had cannot be overstated. The Attorney General’s settlement does a lot for drivers, both in terms of restitution, and improved conditions going forward. However, as long as Uber has been operating, the firm has demonstrated a pattern of breaking laws first and seeing just how much they can get away with. In this case, drivers were able to make Uber pay, to the tune of over a quarter of a billion dollars. But this victory should not overshadow the magnitude of Uber’s disdain for the law.

Cutting Costs by Ignoring Taxes and Labor Protections

The settlement between Uber and New York is a victory for workers, and it seems unlikely that Uber could similarly bilk future New York drivers. However, New York is just one market where Uber operates, and this case of wage theft must be placed in a wider context of Uber’s strategy to lower costs by avoiding paying taxes and workers alike. Multiple US states have taken Uber to court for tax issues. In 2022, a Georgia tribunal found that Uber had avoided paying almost $9 million in sales taxes, and ordered the company to pay up (Jardine, 2022). Uber faced a similar issue in Ohio in 2018 (Schiller, 2018). New Jersey demanded $100 million in back taxes from Uber: a nontrivial sum, but it pales in comparison with the states original ask of $649 million (Metz, 2022). Cases like New Jersey’s demonstrate the viability of Uber’s tax avoidance schemes. In their best-case scenario, Uber could potentially get away with paying nothing. However, even when they are taken to court, there is no guarantee the government will get anywhere near what Uber initially avoided paying. Around the world, Uber has exported its business model of extracting surplus value by ignoring worker protections.

Back in 2014, as Uber began its campaign of wage theft in New York, it was recruiting drivers in Finland without telling them that they could be charged for illegally operating a taxi. After over a hundred and twenty drivers were charged with that very crime, Uber did not provide any legal assistance or reimbursement for fines, Finnish national broadcaster Yle reported. Later on, in 2020, Italy placed the local division of UberEats under judicial supervision after L’Espresso revealed that the delivery wing of Uber had been underpaying delivery workers, and allegedly stealing their tips. Elsewhere around the world, Uber used lobbying campaigns, media charm offensives, and anti-law enforcement technologies to establish itself across the global market (Medina & Sadek, 2022). Uber’s philosophy of asking for forgiveness rather than permission is not limited just to the United States.

Conclusion: Sea Change or Same Old Story?

The New York Attorney General’s ruling did not come in a vacuum. Uber is beginning to face more heat in the United States, especially when it comes to the classification of their workers. The New Jersey case, in which Uber was required to pay $100 million, hinged on the court’s redefinition of Uber drivers, from independent contractors to employees (Metz, 2022). A similar case is currently being heard in Massachusetts (Lisinski, 2024). These cases are long overdue, and their outcomes will have lasting impacts on not just Uber, but many other corporations that rely on the gig-economy model. By ensuring that drivers are classified as employees, thousands of workers in the United States stand to gain unemployment insurance, healthcare, and better working conditions.

The increasing pressure on Uber to recognize its workers as employees, and not independent contractors, could help ensure Uber does not take advantage of its workers like it did in New York City. The Attorney General’s settlement is a huge victory for drivers in New York, and not just the ones who had their wages stolen. Drivers will enjoy a higher pay rate, and more stringent protections designed to prevent crimes like this from happening again. Thus, drivers in New York are much less likely to suffer from a similar case of wage theft, whether from Uber or any other rideshare company.

Matthew Cole notes in Jacobin that the successful suit against Uber, and the new working conditions won in that battle, are part of a continuing trend in the labor movement. Not only are workers trying to protect their interests by organizing against their employer, but they are also seeking to change or reinterpret labor laws to the benefit of workers. Los Deliveristas Unidos, who deliver food for UberEats and other delivery apps, won their own victory with a new, increased minimum pay rate for delivery workers, instituted by the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (Cole, 2023). This process is is all the more important in the gig eocnomy, which has ushered in a reorganization of the worker-employer relationship. For years, the chaos caused by that reorganization has favored capital. The victories of NYTWA and Los Deliveristas Unidos could represent a change in the prevailing winds of the labor movement.

However, Uber has been breaking laws as long as it has been doing business, and the terms of this settlement are limited to New York. The cases in New Jersey and Massachusetts widen the scope of Uber’s battles somewhat, but those are two jurisdictions that, like New York, are seen as worker-friendly. Uber is now a global company with a well-developed international lobbying apparatus. While New Yorkers can and should celebrate their new victories, there will be more fights to be fought against Uber, and workers and the organizations that represent them must not grow complacent on the basis of a few successful lawsuits.

Works Cited

Browning, K., & Ley, A. (2023, November 3). Uber and Lyft agree to $328 million payout for New York drivers. The New York Times, B3. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/02/nyregion/uber-lyft-drivers-wage-theft-payout.html

Chen, B. (2012, December 3). A feisty start-up is met with regulatory snarl. The New York Times, B1. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/03/technology/app-maker-uber-hits-regulatory-snarl.html

Chen, N., & Khafagy, A. (2023, November 16). Uber and Lyft wage theft settlement explained. Documented. https://documentedny.com/2023/11/16/uber-lyft-wage-theft-settlement-explained/

Cole, M. (2023, November 8). NYC cab drivers just sued Uber and Lyft for hundreds of millions in unpaid wages. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/11/new-york-cab-drivers-wage-theft-suit-gig-work-organizing

Conger, K. (2017, May 31). New York drivers say Uber still owes them millions more. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/new-york-drivers-say-uber-still-owes-them-millions-more-1795697568

Flegenheimer, M. (2012a, September 7). For now, taxi office says, cab-hailing apps aren’t allowed. The New York Times, A26. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/07/nyregion/cab-hailing-apps-not-allowed-by-new-york-taxi-commission.html

Flegenheimer, M. (2012b, October 16). Taxi-hailing app pulls out of New York after 6 weeks. The New York Times, A24. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/17/nyregion/taxi-hailing-app-uber-pulls-out-of-new-york-after-6-weeks.html

Griswold, A. (2015, November 18). Uber won New York. Slate. https://slate.com/business/2015/11/uber-won-new-york-city-it-only-took-five-years.html

Isaac, M. (2017, February 23). Inside Uber’s aggressive, unrestrained workplace culture. The New York Times, A1. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/technology/uber-workplace-culture.html

Isser, M. (2023, February 13). Employers steal up to $50 billion from workers every year. It’s time to reclaim it. In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/wage-theft-union-labor-biden-iupat

Jardine, C. (2022, November 14). Georgia tribunal says Uber owes millions in unpaid sales tax. TaxNotes. https://www.taxnotes.com/featured-news/georgia-tribunal-says-uber-owes-millions-unpaid-sales-tax/2022/11/11/7fcpg

Lehrer, B. (2023, October 20). Why NYC lifted its cap on rideshare cars. The Brian Lehrer Show. WNYC. https://www.wnyc.org/story/why-nyc-lifted-its-cap-rideshare-cars/

Lisinski, C. (2024, May 13). Mass trial over whether Uber, Lyft drivers are independent contractors begins Monday. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/news/2024/05/13/uber-lyft-trial-independent-contractors-employees

Medina, B., & Sadek, N. (2022, August 2). Highlights from Uber Files reporting around the globe. International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. https://www.icij.org/investigations/uber-files/highlights-from-uber-files-reporting-around-the-globe/

Metz, C. (2022, September 12). Uber agrees to pay N.J. $100 million in dispute over drivers’ employment status. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/12/technology/uber-new-jersey-settlement.html

Offenhartz, J. (2017, May 24). Uber owes millions to NYC drivers after admitting to accounting mistake. Gothamist. https://gothamist.com/news/uber-owes-millions-to-nyc-drivers-after-admitting-to-accounting-mistake

Office of the New York State Attorney General. (2023, November 2). Attorney General James secures $328 million from Uber and Lyft for taking earnings from drivers. https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/2023/attorney-general-james-secures-328-million-uber-and-lyft-taking-earnings-drivers

Paybarah, A. (2019, May 21). Taxi industry leaders got rich, drivers paid the price. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/21/nyregion/newyorktoday/nyc-news-taxi-medallions.html

Robbins, C. (2013, June 6). Green “boro taxis” & e-hail apps are alive, thanks to courts. Gothamist. https://gothamist.com/news/green-boro-taxis-e-hail-apps-are-alive-thanks-to-courts

Rosenthal, B. (2019, May 19). ‘They were conned’: how reckless loans devastated a generation of taxi drivers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/19/nyregion/nyc-taxis-medallions-suicides.html

Rosenthal, B. (2019b, May 19). As thousands of taxi drivers were trapped in loans, top officials counted the money. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/19/nyregion/taxi-medallions.html

Scheiber, N. (2017a, May 24). Uber to repay millions to drivers, who could be owed far more. The New York Times, B1. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/business/economy/uber-drivers-tax.html

Scheiber, N. (2017b, June 2). Uber says it just noticed error on pay, but it was no secret. The New York Times, B3. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/01/business/uber-driver-commissions.html

Schiller, Z. (2018, February 14). Company hasn’t been collecting sales tax, as it should. Policy Matters Ohio. https://www.policymattersohio.org/press-room/2018/02/14/state-to-uber-pay-up

Taxi & Limousine Commission. (n.d.). Monthly data reports. City of New York. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://www.nyc.gov/site/tlc/about/aggregated-reports.page

Wortham, J. (2011, May 4). With a start-up company, a ride is just a tap of an app away. The New York Times, B6. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/04/technology/04ride.html

Leave a comment