Akira Kurosawa’s indictment of Japan’s chauvinistic worldview

At the conclusion of World War II, Japan was a country in peril. In the last couple of years, it had been bombed and bankrupted to the point of widespread poverty, starvation, and ruin. A total defeat had Japanese soldiers returning to their homes restless and demeaned. The American occupation of blighted Japan further depressed the morale of the public.

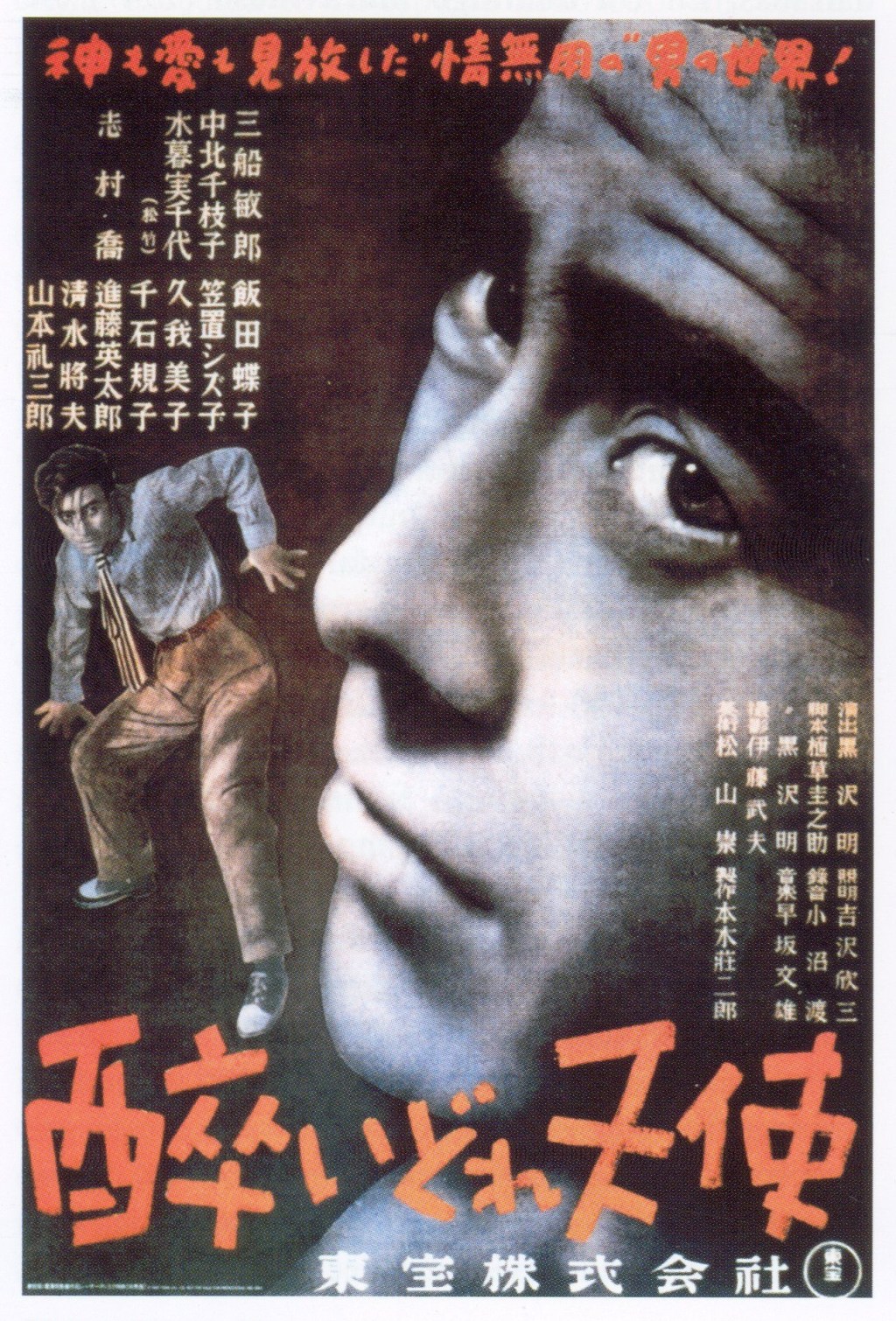

Two years after the war, Akira Kurosawa released Drunken Angel, a story focused on a young gangster and an aging doctor. More than that, however, Drunken Angel is a snapshot of the destitution of postwar Japan, as well as an exploration of the root causes of Japan’s nationalist streak in the first half of the twentieth century.

Drunken Angel primarily deals with the relationship between Matsunaga (Toshiro Mifune), a young and bold Yakuza, and Sanada (Takashi Shimura), an aging, cynical doctor, as well as the titular drunkard. Matsunaga is one of those young Japanese men who has come back to a Japan in shambles. Their unsteady relationship begins in the first scene as Matsunaga comes to Sanada’s clinic seeking help for a bullet wound. After Matsunaga complains of a persistent cold, however, Sanada checks him for Tuberculosis, a common disease in postwar Japan. When Sanada warns Matsunaga that there is a hole in his lung, Matsunaga lashes out, literally, and leaves Sanada stunned on the floor.

Matsunaga’s response, a refusal to address an unavoidable problem, is a reference to Japan’s culture of militarism and extreme loyalty, referred to later by Sanada himself as “feudalism.” Instead of foregoing women and alcohol as instructed by Sanada, Matsunaga leans into those vices as a coping mechanism for his stress and pain. The parallels with Japan’s culture of loyalty and bravado are further made clear by the appearance of Okada (Reisaburo Yamamoto). Okada is a more senior Yakuza member, one who had been in prison for nearly four years. During that time, Matsunaga had grown in power and influence, and had effectively replaced Okada on the street. Now that Okada had returned, Matsunaga had to welcome him back as a compatriot without “losing face.” This placed even more pressure on Matsunaga to assert himself, which he does by drinking and womanizing. This, of course, leads to Matsunaga’s dramatic and painful downfall in a famous fight scene with Okada.

As the movie closes, Sanada mourns Matsunaga with Gin (Noriko Sengoku), a woman who admired Matsunaga and wished for him to move with her to the country. As they stand by the cesspool, a schoolgirl (Yoshiko Suga) whom Sanada has been treating for TB approaches and joyfully tells him she’s been cured.

Kurosawa made created the interactions between his characters very deliberately. Matsunaga is a Japan that is rotten at its core, like Tuberculosis, like a cesspool in the middle of a neighborhood. Sanada preaches moderation to him, but Matsunaga is bound by his honor and face to serve Okada. Okada is driven by greed, and uses Matsunaga’s loyalty to his own advantage. This is the dilemma that Japan itself faced in the years leading up to and during WWII. Japan had a culture bound by honor and loyalty which wouldn’t listen to antiwar moderates. Instead, militarist rulers used Japan’s culture to draw the empire into wars of expansion in Asia, culminating in the total war that took place in the Pacific and mainland Asia during WWII. Sanada represents a moderate voice in Japan that was powerless to do anything but stand by as the country careened into military conflict. Japan’s militarist culture brought about its own violent destruction.

As the old traditions of Japan are mourned, Kurosawa looks to the future, shown by the schoolgirl, ignorant of the mournful air around her, cured of the same disease that afflicted Matsunaga. She is Japan’s future, and Kurosawa quite intentionally characterized her as happy, energetic and carefree.

Kurosawa’s critiques of Japan were not hidden. Sanada tells off Matsunaga outright about his destructive behavior, criticizing especially his obsession with maintaining face instead of recovering from his sickness. What Kurosawa did have to hide, however, were his critiques of the American occupying force.

Many Americans may not realize that the United States occupied Japan for years after WWII. Until 1952, the US was in charge of Japan, and the occupying Americans didn’t hesitate to flex that power. As such, every movie released in Japan had to pass through American censors. Kurosawa was not allowed to show bombed out buildings, even though much of Japanese cities were leveled by American bombs. Instead, he used the cesspool in the middle of the neighborhood to show the postwar dilapidation. Kurosawa also wanted to use the song Mack the Knife as a recurring motif, but the censors wouldn’t allow a connection to Germany. (The original lyrics are in German.) He did manage to get some things by the censors, however, most notably a scene inside a jazz club. Matsunaga dances in a club to live music, sung by Shizuko Kasagi, a Japanese singer famous at the time. The song, “Jungle Boogie,” pokes fun at American jazz with lyrics about a fearsome tiger-woman.

Kurosawa also chose to dress the various Yakuza and their female companions in Western clothing, while Sanada wears more traditional Japanese clothes. Matsunaga drinks whiskey, while Sanada drinks sake. (And medical alcohol. The movie is called Drunken Angel for a reason.)

Drunken Angel is much more than a simple Yakuza movie, as popular as those were in Japan after WWII. Akira Kurosawa manages to lament the descent of Japan into international violence, critique its culture of honor and loyalty, and condemn the conditions of Japan under occupation all in one movie about a gangster and a doctor. Drunken Angel is not Kurosawa’s most famous, or best received movie. Indeed, Kurosawa is much better known for his Samurai films like Rashomon and Seven Samurai. However, few of his movies allow him to create such a biting and relevant message as did Drunken Angel.

Further Reading:

- Drunken Angel: The Spoils of War. Ian Buruma, The Criterion Collection

- Three Early Kurosawas: Drunken Angel, Scandal, I Live in Fear. Gary Morris, Bright Lights Film Journal

Leave a comment